Is chronic pain just a function of our brains? If so, how do we change our perception of pain? Today, we speak with licensed clinical psychiatrist and pain researcher Dr. Afton Hassett, author of Chronic Pain Reset: 30 Days of Activities, Practices, and Skills to Help You Thrive. Throughout her career, Afton has delved into the connections between the brain, chronic pain, physical activity, and emotion. She remains at the forefront of her field, and in our conversation she shares with us several of her favorite takeaways from her most recent book. Those of us intimately familiar with chronic pain know just how severely it can impact quality of life and happiness. With that in mind, join us to learn new, game-changing pain management strategies and therapies.

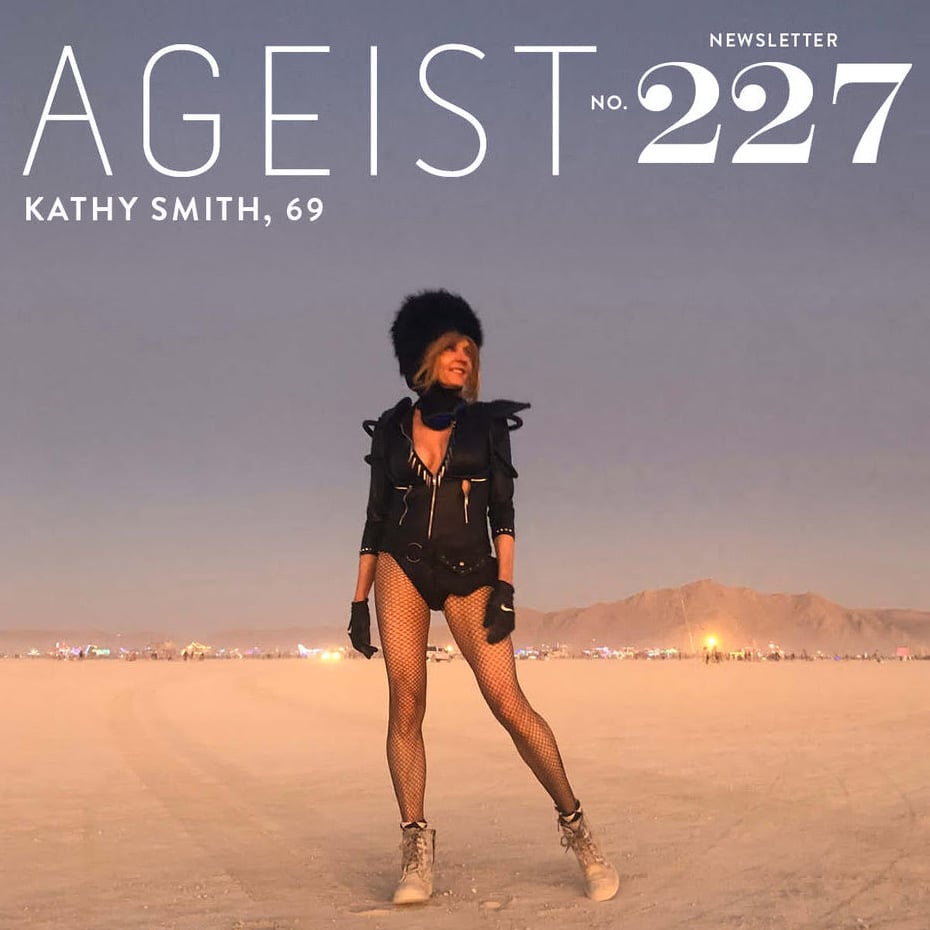

What kind of SuperAger are you? Take our quiz today and find out! Visit ageist.com/quiz. Dr. Afton is a Fox!

Thank you to our sponsors:

Ned Mellö Magnesium — essential supplement to improve sleep, reduce stress, increase energy, and more. Use code “AGEIST” for 15% off at helloned.com/AGEIST

InsideTracker – the dashboard to your Inner Health. Listeners get 20% off on all products at InsideTracker.com/AGEIST.

Timeline Nutrition — our favorite supplement for cell support and mitochondrial function. Listeners receive 10% off your first order of Mitopure with code AGEIST at TimelineNutrition.com/ageist.

Key Moments

“A little bit of pain is proper. What happens, though, is pain can change from being something like a stimulus response, meaning that you burn your finger and you experience pain, and it can turn into something that’s not just pain experienced by a burning finger. And the brain, sometimes the brain actually creates the experience of pain.”

“What we see in chronic pain is that the default mode network is talking way too much to another network called the salience network, which is a network that says: Hey, pay attention, this is really something big, watch out. And so, these two networks are over connected. And so, what we look for sometimes in interventions is: Does the treatment actually start disentangling these two networks?”

“So, when we define pain, pain is a sensory, it’s an emotional and it’s a cognitive; it’s a thought derived process. Pain exists because there is this awareness of it. So when people are anesthetized, you don’t feel pain.”

About Dr. Afton Hassett:

Chronic Pain Reset: 30 Days of Activities, Practices, and Skills to Help You Thrive

LinkedIn

Bio

Transcript

David: 0:15

Hey Afton, how are you? Great to have you on. You have a new book called Chronic Pain Reset. I’d like to learn a little bit about your background and how you came to be interested in pain.

Afton: 0:33

Oh great. Well, it was not a straight line how I got here. I actually was interested in just becoming a regular psychologist and became interested in pain when I was early in my training. I was working with these women who had depression and other conditions, autoimmune disease and a number of things, and what would happen is, whenever we’d make some progress in therapy, their pain would worsen. And it became fascinating. How is this working? We’re making progress or things are getting worse and your pain is worsening. And so my very smart supervisor, Martha Chouax, said you know what, if you really want to understand this phenomenon I think you’ll like this. Why don’t you go to the UCSD library? I was in San Diego at the time. So the University of California, San Diego go to their medical library and pull some articles on fibromyalgia and chronic low back pain and just read about them. And so this is the olden days. And so I went to the physical library and fold books off the shelf and read these fascinating medical articles about the interplay between behavior, thoughts, the experience of pain, brain. I mean, it was just such a wonderful, fascinating combination that felt like wow, you can influence the actual experience of pain by how you think and how you feel and I was just the possibility that was true, got me hooked, and so, about 20 years ago, I changed my dissertation and I moved towards the direction of chronic pain and, and since then I’ve been absolutely blessed to join the team at the University of Michigan. The chronic pain and fatigue research center, where I’m a principal investigator at, is one of the premier research sites in the world studying chronic pain. We’re within the Department of anesthesia at the University of Michigan.

David: 2:22

So when I think of anesthesia, I think of drugs, heavy drugs. I guess maybe we should start with what is pain yeah.

Afton: 2:30

Wow. So pain is kind of our warning system. Pain is a good thing. So when we injure ourselves and experience pain like we put our hand on a hot burner oh my gosh we pull our hand back really quickly, which is great, because if we left our hand there on the hot burner it would be very, very bad. Right and pain, when it happens like a twisted ankle, it tells you stay off of this, don’t aggravate this, let yourself heal. You know, retire, regress it back. So people who don’t have pain receptors often don’t live very long. Right, they get themselves into all sorts of precarious situations because pain is not there to warn them away from bad things. So a little bit of pain is proper. What happens, though, is pain can change from being something like a stimulus response, meaning that you burn your finger and you experience pain. It can turn into something that’s not just pain experienced by burning finger and the brain it detects it to the brain actually creating the experience of pain. So, over time, the more you experience a single pain signal. So let’s say, you have a really bad knee, you got osteoarthritis to the knee and it’s grinding, it’s grinding, it’s grinding, it’s pain and pain and pain, and six months later. Your body’s been sending this pain signal for six months almost continuously. Well, we have an axiom in neuroscience neurons that fire together wire together. So the more we repeatedly experience something, the more likely your central nervous system will remember it and more easily do this, and so the pain coming from that nasty knee becomes almost a natural experience. That happens almost on its own, and this is a form of pain that we know as no-sea plastic pain, meaning that the pain is experienced as a changing in the plasticity of your brain that your brain has rewired and now is actually either enhancing that pain or making that pain worse, and so that’s a very different pain experience than when you have a boo boo, when you hurt yourself and know you need to stay off of it. Then, when you have the brain, it’s actually creating the pain, and that’s the type of pain we see very frequently in many chronic pain conditions like fibromyalgia, chronic low back pain, temperamentibular joint disorder and even like things in the gut, like inflammatory bowel disease or even irritable bowel syndrome. So even these autoimmune diseases like inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis and lupus can all create this brain-driven pain.

David: 5:07

If I understand this correctly, what I’m saying is the stimulus is removed, but the pain signal remains.

Afton: 5:16

You got it right. You’ve heard of phantom limb pain. Yes, right, you familiar with that concept, that where somebody will have a leg amputated or a part of the body amputated and then they report for sometimes years that that limb is on fire, that it still hurts, that it’s incredibly painful, but the limb is not there. The representation of limb does remain in the brain and as long as that representation is in the brain, the brain is sending that signal. Oh, that limb hurts and you’re like it’s not there. How is my foot hurt? It’s not there Again. It is one of the brain’s way that it rewires. It represents parts of our body and then it can create pain really on its own, or at least amplify pain.

David: 5:59

We’ve had people come on and they talk about the default mode network, how it’s the default in the brain that when we’re not doing anything else it just goes to whatever that ancient wiring is, and it’s often really helpful to reset that. Is that part of what we’re talking?

Afton: 6:18

about here? I’m glad you asked because it is. So. The default mode network is really what’s kind of motoring along when we’re just kind of thinking self-referential thoughts, when we’re kind of thinking about daydreaming and what we can do and thinking about your body and you know what’s my back doing. That’s just kind of default mode network. What we see in chronic pain is that the default mode network is talking way too much to another network called the salience network, which is a network that says, hey, pay attention, this is really something big, watch out. And so these two networks are over connected. And so what we look for sometimes in interventions is does the treatment actually start disentangling these two networks? And that seems to coincide with people say, hey, I’m experiencing less pain, so these two networks are slightly disentangled. So yeah, you’re on the mark.

David: 7:15

I don’t see it. Yes, I have no idea. It was a good guess. I want to go back to sort of classic pain treatment which are opioid based painkillers, which I personally hate. I mean, you don’t have to like. I’ve had boredom removal of helicite and stuff and I would rather have pain in the way I feel. I’m just one of those people. But what is it that opioids do in this whole scheme?

Afton: 7:42

So opioids are wonderful drugs for certain conditions. They are so powerful for surgery, dental surgery, physical body surgery, an acute accident You’ve been squashed in a car accident and you’re in terrible pain cancer pain, phenomenal drugs to treat this really acute driven pain by some sort of injury, and there’s almost nothing better right to actually give relief. Where the problem tends to come is for conditions like chronic pain, where we think they’re predominantly either driven by the brain or they’re driven by inflammation or some other process. The opioids can be helpful for some people and really not helpful for others. And there really are few good studies that show that opioids are helpful at all for chronic pain. There’s some short term studies that maybe short term it can be helpful for somebody who has newly diagnosed chronic pain, maybe can help initially, but there are no studies about long term opioid therapy. And so what we’ve learned over the years? We treat 2000 patients a year through our clinic, new patients every year coming through our clinic at University of Michigan in our department, and many people come in on opioids. But they come in saying, hey, I’ve had chronic pain for eight years, I’ve been on opioids for two years and my pain is still a seven, if you take me off of opioids, my pain will be 107. And you’re like, okay, that could be true or might not be true, because what we do know is that anytime we put something into our body that’s not natural, the, if it is something that our body makes itself, like endorphins or cannabinoids or or dopamine If you put that in the form of pills and medications, your body just stops making it, it just slows down making it, so doesn’t make its own endorphins to make you happy. It doesn’t make its own dope dopamine, so you feel reborn and joyful. It doesn’t make cannabinoids, so you feel peaceful and not nauseous. And that’s why, when people go off these medications, they have all sorts of side effects, and now the body doesn’t know what the heck is going on. It’s got to make stuff again and it’s and you know, at least to all the really bad side effects that we see. So what we want people to do when they’re on these medications is to see what’s going on, because sometimes one of the things we see when people on opioids for a long time, they’re endorphins change and now they’ve actually in many cases created a situation where the opioids themselves are making the pain worse. It’s something we call opioid induced hyperalgae. It means that your pain now is being driven by the fact that you’re on opioids and if we take you off opioids you’ll be shocked In many cases that your pain is better. And so what we really recommend is that if people come in on long term doses of opiates we don’t know if you’re a benefitter, because there are some people that do benefit on long term opioid therapy or we don’t know if you’re going to be a million percent better. So the people who we think you know have been on long term opioid therapy, we try to get them to ween off and we do that with, you know, with other treatments, other medications and teaching behavioral things and giving them other, you know other things to keep them comfortable and and see what we have. And what we often see is, about four weeks after being off the medication, patients are like my pain is better. How is my pain better? I’m off of opioids and I can think well and my emotions are back and I’m sleeping better and everything is better. So you know, doing this opiate experiment can really be life changing for some people on long-term opiate therapy if they take, if they’ve chronic pain.

David: 11:37

Talk to me about say somebody has a problem. They have a problem the disc in their back. Yeah, back pain hurts. Yeah, they have trouble sleeping, can’t move around well.

Afton: 11:47

So you know when, when you have something like a disc, I say you’ve gone into your physician, you say my back is terribly painful, they send you for an MRI and they show oh my god, you got a great big, bulging disc. And at that point the decision that the physician makes is you know, do we send you to surgery and maybe get this thing fixed? And for some people that’s a total miracle. Right, they go back in, they fix the disc and Pain is better. For some people, though, they have a bit of bulging, bulging discs. They go and they get their surgery and then they come out. They’re like my pain is the same. How is that possible? You fix the disc and my pain is the same. This happens with arthroplasty, with the people with knees get a knee replaced and they come out the other end, they do all the rehab and they’re like my knee hurts just as bad as it did before the surgery or my hip. So what is happening? Again, this is no seplastic pain. Can it form in all of these situations? So it could be secondary to the disc right, so the disc could be driving this. No seplastic pain too. So you might have disc hurt and brain pain driven hurt at the same time. But what’s even more remarkable is that when we do studies of MRIs, to the pain that people report, there’s almost never a Correlation, meaning that people who have terrible looking X-rays or MRIs of their knees, their back or their neck Often don’t report pain. I have horrible knees, I have osteoarthritis of the knees. That is beyond belief. And I feel no pain in my knees. I didn’t know that because I broke a knee and my in my position they did they the image both of my knees. They said you have terrible osteoarthritis. How do you get around? I don’t know, but this is something we see all the time. And then other people can have Really unbelievably join unbelievable joint pain. They’re going to get MRI. The doc’s like I don’t see anything. I don’t see anything. And so the correlation between what we see on MRIs and what the actual Experiences often doesn’t match. And we’re actually conducting with the largest studies right now across 14 sites to look at Patients who have chronic low back pain, who have been, you know, have reported every kind of way, shape or form of pain, and then having two Radiologists, we read all their back scans and so we’ll be able to say definitively how frequently this happens, this mismatch between the mess in your back and what you feel, because that person who has that horrible looking back their pain could be due to a the disc, or be due to the brain, or see, due to the brain and the disc. So, and all of these need different treatment and the bug of it was what do you treat? How do you do it?

David: 14:31

So tell me about this. So tell me what’s the? I Guess we’re just Discriminating between sort of two kinds of things going on here. So there’s an acute pain. I recently had knee surgery. They gave me some oxy. I didn’t take it because I hate that stuff and like some ibuprofen was fine, but they gave that to me just in case they said, listen, you might have like a pain level of 9, we don’t know, but it’ll go away. So that would be sort of an acute thing. And then we have someone who has something that will say longer than I don’t know, a couple weeks, something like that. As part of this question, I want to ask you how long does the pain signal needs to go on for the brain wiring to happen?

Afton: 15:10

Yeah, no, great question. So the chronic pain we consider greater than three months, right, so somebody has a, has a nasty ankle pull and they continue to have severe crying pain, you know longer than, or you know Like, three months. Then we say that that’s not, that’s no cry pain. That has kind of crossed the Rubicon, and then we feel a little more confident that now the brain has rewired. But the crazy thing is the brain rewires really fast. So an example I keep in my I have in my book is a study was recently published, in the last year, and what they did in this study Is they wanted to see how fast does the brain rewire, and so they had a group of Individuals cast their arm right, so they put these cat, these cast on their arm and so they could not move their arm at all. And then they did like an fmri, a neuro image, every day, just about every single day, and watched what the brain was doing. And what they observed is that the part of the brain that processed all the movement in this arm, all those little neurons, went dormant. They just stopped working and they were no longer firing because this was now dormant, and so that happened within like a week. So the rewiring happened within a week. But then, what was incredible, when they uncasted the arm, the neurons were just kind of like, almost like idling. And then the second, the arms started moving in. They all popped back into life. And so it just tells us, our brain is so plastic, way more plastic than we ever thought before. So that opens the door that this rewiring of having more pain could happen pretty fast. But then we can also change the wiring also pretty fast by doing different things, by adding different inputs.

David: 16:49

So in the cast experiment neurons go off. Take the cast off the neurons, sort of like, ah, something’s going on here, and then they wake up and they go. But yep. Which is wonderful. But if we have something that’s more locked in Nerves, that fire together wire and the and now they’re wire, yeah, now the pain signal is removed, but the wiring is still there. So there, so with that. So now, how do you deal with that?

Afton: 17:15

Yeah, we have to kind of sneak up on it. So what we know, that’s in our, in our purview, things that we can do. There’s many things that we do that help change our brain health Eating well, exercise, sleeping well that sets the environment for us now to be able to influence, because we’re kind of dealing with brain health and that helps with you know, create new connections. When we’re eating well, sleeping well and exercising, exercise is probably the best thing and that doesn’t mean gym, going to go in the gym, let me just walk and get outside. All that kind of stimulates helpful. But the other thing that we have in our little arsenal is that our thoughts and our emotions also greatly impact our feeling of pain. So when we define pain, pain is a sensory, it’s an emotional and it’s a cognitive, for it’s a thought derived process. Pain exists because there is this awareness of it. So when people are anesthetized, you don’t feel pain. When they’re doing the surgery right. Once you wake up and you’re processing, you’re aware, you’re emotional, you’re everything’s there, you feel the pain. The other piece is that the parts of our brain that process our thoughts and our emotions, the same networks, overlap very well with the pain network. So you might notice that if you’ve ever injured yourself and you get afraid or really angry, the pain can be worse Again. It’s just a stress response, it’s stimulating, it makes the pain worse. If you’ve ever been in a really fun game playing volleyball with people, maybe you tweak your ankle a little bit. But you just play the rest of the game and you’re having a blast. And then at the end of the game you’re like oh my God, wait a second, I’ve really hurt my ankle. You know, again, the positive emotions and distraction keep you away from even feeling, even really detecting that pain. So our emotions and our thoughts greatly impact the experience of pain.

David: 19:03

So my thought here on this in my experience, my personal experience, is a two-way thing. So if I feel pain, I get grouchy, I also. I’ve noticed I can’t think as clearly.

Afton: 19:15

It’s both right so again, it’s all of the networks. And so there was a big kind of belief early on, within 20 years ago or even recently, that chronic pain is a psychiatric condition. Because depression and its anxieties are so common, it’s got to be depression, it’s got to be a psychiatric condition. It’s not true at all. It really appears more so that pain kind of creates the environment where people become anxious and depressed. And so you know it’s not that there’s, you know that there’s this psychiatric condition, and when manifestation is pain it seems to be the other way around. And then we have shown this in a really interesting pair of studies that we did in children, and so it came from a larger NIH effort called ABCD, and it’s where they’re following a lot of children and it’s funded by NIDA, which is the National Institute that Looks at Drug Abuse, and what they’re questioning is that what are the processes that put people at risk for substance abuse down the road? But we also have to ask a question about pain, and so they do ask a lot of questions, and so we have children that are followed over years, that not only complete a lot of questionnaires themselves and their parents, but also get neuroimaging every year, and so we can watch the child brain change right. And so what we determined is in the first paper. We looked at the children in the state database and followed them over time and found that what predicted the onset of pain when they were older adolescents was not depression and anxiety. That didn’t set the stage for it. Instead it was having a lot of sensitivity in the body, being aware of the body, having some cognition problems because she was just saying how your thoughts get all screwed up, having some cognition problems on the front end, some sleep problems. That’s what predicted. And then the thing that was so exciting too is in the neuroimaging and remember those brain areas we talked about Default mode network, talking to the salience network that we see as a problem in adults with chronic pain, that same dysfunction in children before they had pain we saw the same level of connectivity before the pain and there the children most likely to get pain down the road. So it’s almost like the wiring is kind of there waiting.

David: 21:31

Wow.

Afton: 21:31

We’re looking at this too. So I have a colleague at the chronic pain and fatigue research center called Kevin Banky who does research in psilocybin and cannabis, and so he’s kind of our guru of controversial substances. But the thought is, the way that psilocybin works not unlike ketamine is that by taking it there is a rewiring. The wiring kind of gets reset, and that perhaps helps us explain why psilocybin can help with PTSD, or ketamine can help with PTSD because it disturbs some of those circuits. So we’re studying that in pain. I’m more on the outside of those studies, I’m just an observer like all the rest of the scientists, but it’s fascinating Again. It’s like how do we change these networks that are not helpful? And the whole gist of the book is that there are all sorts of things that you can do, these little things that you can do that set the stage for enhancing and changing actually how your brain is processing the experience of pain.

David: 22:36

I was having some sort of referential pain, so not actual pain. So they remove the desk or whatever the surgery is, but I still have this pain feeling because of the wiring. What are the top five things you would have?

Afton: 22:50

Great question. You set me up perfectly. So the first question I always ask if I’m seeing a patient is like how are you sleeping? Right, that is a big one. So if somebody isn’t sleeping well, that’s our low hanging fruit. Let’s get you sleeping well again, not on drugs, let’s do some behavioral things and get you sleeping. We do so many things to mess up our sleep. That’s the first thing we all do. So looking at our devices at 10 o’clock at night, that’s like getting yourself a blast of sunshine. There’s a party of brains that says, oh morning, there’s so many things we can change. The second thing that I am very interested in is are you exercising? Are you moving? So what happens very often when people have chronic pain, they get the part fixed. They’re already really deconditioned, so their muscles are achy and crampy anyway and they’re now out of the habit of getting any exercise. So get people moving, get a Fitbit, get out there, do an extra 10 steps a day, every day. Get out in nature, because the data of how well our brains do and our bodies do, just exposed to nature, even sitting on your patio in front of vegetation, is helpful. We need that. We need green space. We need to get out and have the wind in our hair and smell fresh air and get a little sunshine on the face. It’s critical, but then I look at stress. So stress is a killer and the brain is very sensitive to threat and our brain is pretty much wired to watch for threat. That’s what we do. We scan the environment and if something is perceived as stressful, we have a biological reaction to it, and in that biological reaction we actually make our pain worse too. So I want to get people to be better at coping with their stress, and so it’s great to teach people some mindful breathing, some ways to think about dialing town stressful thoughts. Many people have thought patterns, rumination and other things that are not helpful, that make you feel threat, and so we try and do that, and then one of the most powerful things too, is distraction, so finding things that you really enjoy, a hobby you love, something that’s totally engaging. So you’re just getting this state of flow and losing yourself. When you’re in that state, you don’t feel pain because your attention is in this thing. It’s very deep, and so the more that we can introduce things that are not pain, the more we start to break those bonds, the more that we introduce positive emotions and get this other part of our brain working, because part of the dysfunction in chronic pain is another part of the brain, the part of our brain that processes reward and pleasure, that tends to get dysregulated too. So many people with chronic pain also have kind of depression. They just feel meh, then nothing is very appealing. They don’t want to do anything fun, and that really is, because that is a network dysfunction. That’s reversible too by just getting people out and again and connecting with other people, and, joyful and again, you just start building this reward up. This is not unlike what we see with people who are off of addictive substances like crystal, methamphetamine or some such thing. That part of the brain kind of gets stymied, it stops functioning. So that’s the hardest thing is to get people to start to feel real joy again, joy from the body as opposed to joy from the substance.

David: 26:03

Is this what’s known as pain recrossing therapy?

Afton: 26:06

So that’s a little bit in the neighborhood. So pain reprocessing therapy is built on the notion that gnosis, plastic pain is probably underlying a single person’s pain. The way that we kind of know that it might be a pain that responds to this therapy is if somebody says, hey, I have death-defying pain, just spectacular pain in my neck, but sometimes it’s gone. And then I will be driving down the road and it’s back and my neck is on fire and I can’t breathe and I am afraid to move, and then it’ll be there for a few days, I can’t move, and then it just subsides, it gets a little bit better, and so people assume it’s a disc or some darn thing is driving this. This is probably one of the most clear manifestations of brain-driven pain. When somebody has some injury, the pain doesn’t come and go. If you’ve broken a leg, you kind of know the pain is pretty much there. It doesn’t come and go, and so pain reprocessing therapy really is built on the notion, then, that what the brain has done, is it at one time was responding to something that was very, very painful and it was telling you be aware, be aware, be aware, because that’s what pain does. Get your hand off of that hot range Beware, beware, beware. But what happens is the brain can get overprotective I call it like an overprotective nanny and it starts just screaming at you when there really isn’t nothing that it should be afraid of. So it might get a little twinge and the brain goes oh my God, quick, jump, move. And so it becomes very, very overreactive. And so pain reprocessing therapy takes this idea and has people who have spoken to their physician. A physician says I don’t see anything on my MRI that tells me that movement is dangerous for you. I want to just start getting some exercise, go to PT, move. And so once people kind of get that okay, pain reprocessing therapy does not much more than tell you a lot of things. I’ve just told you here that the brain is the overprotective nanny and it’s just kind of freaking out. And what we need to do is we really need just to tell the brain that there’s nothing here, there’s nothing to be afraid of, this is okay. And then what we do is we actually have the person move, and so if the person has a neck they haven’t moved in three years, we’ll tell them. Talk to your brain to say it’s all right, I know, there’s no problem and just start moving and usually about a minute into it the person is moving and crying because now it is gone. So not everybody has this pain. We don’t even have a good guess how frequent it is, but for the people that have this type of pain this is like a miracle. Pain isn’t totally gone, it shows up and sometimes it goes to different parts of the body, but the person now knows what’s happening and can kind of do this, whatever this is Cause again it’s just the brain saying watch out, start with your physician. Number one cause you wanna make sure that it isn’t some form of damage that you don’t have God forbid a tumor, or you have something that really needs to be addressed. Pain is there for a reason. It’s there to warn you. So pain does a job. So find out what it is. But if it’s a type of pain that you’ve had for years and that the physician say, hey, you really should be moving, I don’t really see anything here that you know and has been reassured, that you know, get into physical therapy, get moving, then you can think, you know what this may be, the type of chronic pain that I can do more with, right, and so that at that point you want to have, ideally, a physician that’s helping you perhaps a physical therapist is helping you but also doing pain, you know doing your pain, self-management, and that’s really what the book is kind of all about. It’s not just the pieces that you can do to make your pain better, it really is about the pieces you can do to make your life way better. I come from the school of positive psychology. I think about, you know, traditional psychology. I also think about resilient psychology. And how is it that we not only teach people the skills that they need to lessen their pain, to sleep better, to have better relationships, but to actually have a life that is really rich? Because the people who are the most resilient are the ones that actually have some adversity in their life and get past the adversity and actually grow and learn from it. And it’s a big kind of theme in the book is, you know, getting yourself to the next level. You know we all had bad things happen. The question is, do we step back and say, wow, that bad thing actually led me to this thing, which is amazing? And so the book really focuses on really you can get out of it what you put into it so you can learn a few great skills, put them into a work in your life, you know, maybe get yourself moving better, maybe you can do some, you know, corrective actions on your sleep, or you really can maybe revisit your life and kind of think about what really matters and how to lead a life that’s more intentional and more grounding and richer. And I know we talk a lot about aging, but you know, how do we age successfully? How do we apply these principles? Because so many of the principles in this book yes, the whole book really pertains to chronic pain, but many of the activities, skills and practices that people learn in the second part of the book are appropriate to all human beings, because we all do strange things with our emotions. We all think that’s often that are not helpful. We sometimes defeat ourselves with all sorts of you know of behaviors and then you know and we often don’t prioritize which is really important in life so we can lead a long, healthy life.

David: 31:31

So Take away as an agency. Like so many things in life, we don’t always have to accept the grim reality that we can have an impact.

Afton: 31:43

We can make our own reality right.

David: 31:44

Exactly Very good, apton, it’s been wonderful having you on.

Afton: 31:50

Well, thank you. You asked such great questions. You probably got a whole neuroscience lesson that you weren’t ready to have, but I hope pieces will stay with you in your audience and will be helpful.

David: 32:02

Thank you, so much Enjoyed having you today.

Afton: 32:05

Thank you very much.

David: 32:12

So, apton, you took out the super-innocenters, and you and your hands were both excellent.

Afton: 32:18

Yeah, I was excited to be a fox. They were very, very cool critters, but you got to tell me about it.

David: 32:26

I actually wouldn’t assume you would, because you’re very much into medical science. You know, medical science people tend to get into the deep and the deep. Your science needs to be a little more fun. They’re out there, you know, they’re having fun, they realize they control their fellow trivers. And there’s a bunch of other people who are not out there and they’re not as dogmatic. They’re, you know, you think like a fox, sort of like jumping around in the woods. Yeah, that’s what you are. You’re one of them. You’re a super-adurant fox. Congratulations.

Afton: 32:59

Thank you. So I have two sides to me. I’ve got this very geeky kind of science side and I also have the kind of free boot-willing, love life and experience as much as I can. So I guess that kind of makes sense.

The ideas expressed here are solely the opinions of the author and are not researched or verified by AGEIST LLC, or anyone associated with AGEIST LLC. This material should not be construed as medical advice or recommendation, it is for informational use only. We encourage all readers to discuss with your qualified practitioners the relevance of the application of any of these ideas to your life. The recommendations contained herein are not intended to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease. You should always consult your physician or other qualified health provider before starting any new treatment or stopping any treatment that has been prescribed for you by your physician or other qualified health provider. Please call your doctor or 911 immediately if you think you may have a medical or psychiatric emergency.