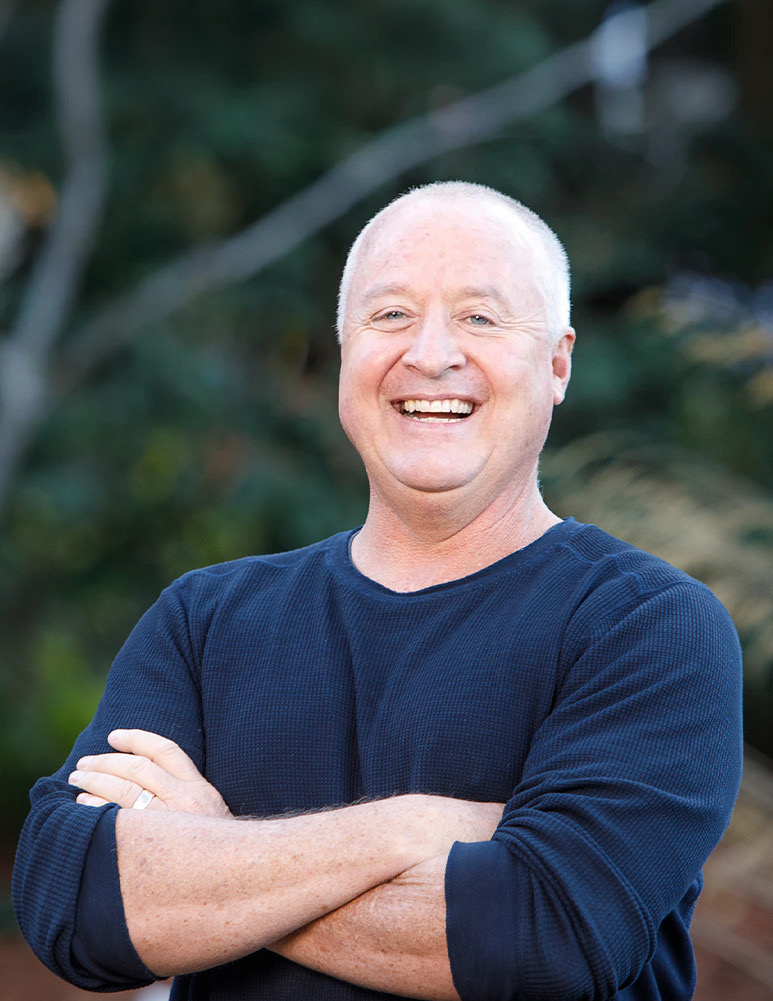

In the world of human performance, Andy Walshe is a legend. He is a humble, soft-spoken man who has made a meaningful impact on the global stage among musicians, dancers, athletes, drivers, business and military people, as a teacher, coach, and savant. His world is the science of human potential in all its facets: physical, cognitive, creative and spiritual. He works to support others on their journeys to achieve their highest. From the US Olympic Team to Red Bull Formula One to really any area of high performance you can think of, Andy is the go-to guy who has designed the programs, built the training centers, and coached the people.

He is now a partner at the mind-blowingly elite Liminal Collective — a group of people habituated to facing and overcoming enormous obstacles, who are now tasked with solving seemingly unsolvable problems. They are tackling big, global problems — cancer, conflicts, and the like. Their method is rooted in humility: first listen and learn from the people they are focused on, then encourage them to listen and learn about themselves and who they can become. To truly go big, it starts with an individual: better you, better team, better world.

The key elements in excellence are curiosity, adherence, and the willingness to try something new and fail. These sound a lot like what we look for in a program to help us later in life. For him, success is not about the outcome, but about maintaining a lifelong beginner’s mindset, which can be challenging as we get older. It turns out that the difficulties a retiring athlete faces are pretty similar to what a 50-year-old faces after being pushed out of a job.

Andy is now thinking about his family, his future. Who does he want to work with, what does he want to achieve, and how does all that intersect with his family life? How will he, as a 57-year-old, be viewed in the world of performance innovation?

Let’s say someone who’s 50 suddenly doesn’t have a job anymore. What would be your advice to someone like that?

That transition is equally traumatic. I’ve been doing X, I’ve been involved in this community for many years, I’ve been part of an institution or movement or whatever it is that you were at, and that’s all part of your job and then it’s gone. The same principles apply. You hadn’t thought of it beforehand, so you were not in a position to make a plan or think about it. Well, what can you do if it just happens and you are sort of caught off-guard? I think in that particular case, we recognize that it’ll be a liminal moment, based on the name of our company. There’ll be a moment where you’ve been who you are, what you’ve been doing, achievement, whatever it may be like by definition, in one space. You’re suddenly thrust into this idea that there’s another version of you, another space you have to step into. And you have to navigate this area in between, which is the liminality that our company is named after.

You’re not who you were and you’re not yet who you’re going to become. And that space is, as you know, characterized by uncertainty, fear, excitement, the whole gamut. The first tip I say to people is just to be patient and kind to yourself in that moment. Don’t try and figure it out because there is no figuring it out. You have to actually — they were saying, “It’s not done to you, it’s done for you.” You have to move through that space, and it can be miserably hard and challenging. I’m not trying to diminish anybody’s responses to that. But I think you have to recognize what it is for and try and use the time and moment to reflect on what was, reflect on who you could become, and then think about what sort of things are really in your mind, where you want to be, and how you want to get there. That all being said, the financial strain, the emotional strain, the loss of community, all of that hits hard. So, I think the other tip I have for everybody is, first and foremost, to reach out to people and ask for help. Talk to people. The 50-cups-of-coffee idea.

Just get out and start talking to people randomly with no agenda. Follow up on your passions; follow up on things you were once interested in, whatever it may be. Be proactive in moving through, even though it’s as horrible and miserable as it can be. And I think all of that starts to help you set up. And that one good friend who can help you navigate that space will make a big difference.

“Be very curious. I think you have to be proactive in that curiosity”

What’s the tactic to expand the imagination of a struggling person, to help them visualize what they could become?

Well, I think that what I already mentioned, that idea of just reaching out to people you know, or may not know, ask for introductions, just explore conversations over a cup of coffee. No agenda, not after a job. Don’t even get that point. Just, “Hey, I’m interested in what you’re doing.” Be very curious. I think you have to be proactive in that curiosity. That part of the process is really important. And then I think the easiest model for how you accelerate that is to go through some reflective exercise.

Now, that could be journaling, could be whatever. But I would encourage people to go, and it will help, get yourself in nature, park, city, somewhere, just get outside, find a quiet place and start to document any of your thoughts, feelings, ideas. If you want to be a bit more directional, think back as a kid: What inspired you? What would you like? What gave you joy? Reflect on moments in your life when you’ve been the happiest, when you’ve been the saddest, when you’ve been inspired. So you start to come up with these moments, and in time you can reflect upon what inspires you about the friends you have, and how you could change things. Slowly, you start to build a bit of a thought board on this whole thing. And out of that we typically see patterns emerging.

That’s really hard because if you’ve been doing one thing for a long time, you probably haven’t had that thought or gone through that thought exercise. What’s their theory of life? Ask: What inspires you? What excites you? What scares you? And get it all down, and then through that process you start to increase the aperture to what’s out there. And in many cases, people report back, “I really did enjoy photography when I was a kid. I had forgotten all about that.” There’s something there. Whether that’s where you go or not, it doesn’t matter. But it’s just the fact that you’re trying to reimagine, based on who you are, what would be a potential opportunity moving forward.

What are your challenges? You’re 57 now; what’s hard for you?

What’s hard for me is on the family side, first and foremost. I had kids late, and by no means in a position where I can just shut down tomorrow and just spend time with them every day, even though that’s what I’d love to do. So my challenges are: How do I create work-life balance? How do I start to make sure I spend the time with them that I really want to? So, I don’t think it’s about this mythical idea of hanging out on a beach together for the rest of our lives. But how do we look at that? How do we balance that? I think professionally that ties. It’s funny that it never even struck me, but in this sort of last post-COVID space, I realized I’ve probably got potentially one other really cool, big inspirational thing I can do in the next 10 years. It could be more, but how at this age do you capture the attention of what you’re imagining going through that same exercise I just outlined? And how would you spend the next 10 years if you could wave a magic wand?

For me, the challenge is balancing the realities of life and the financial side of it with the idea that it probably doesn’t matter what I do. The kids aren’t going to remember that; they’re going to remember: Did I hang out with them? And then in that classic sense, I think most people at our age are like, “You’re not the most hirable anymore.” So, even if you do want to go and do something very different and new, you’re not going to be the latest, greatest graduate. You’re not going to have the latest, greatest knowledge set. You’re going to have wisdom and experience. But if you’re changing careers and trying to do something fresh and new, you’re back to square one.

And you’re used to probably at a senior level having a salary that pays for the mortgage and stuff, and you might have to cut that back. You start to go: “God, is it easier for me to stay in what I’m currently doing and do more of that, or should I take a big step and try something completely new?” And so, navigating all that is challenging right now.

What attracted you to the world of high performance? How did you get from being young Andy to building these high-performance centers?

I wasn’t good enough to actually compete at any level. But I love the coaching, I love the sport in general, and I realized, after getting out of school, that just being outdoors and working with athletes was really exciting.

One thing led to another through a random set of circumstances, and I ended up supporting talent for the Olympics in 1992. I just got hooked into the idea of training and preparation, all the science behind that at the Olympic level, and then just went from there.

I realized that there was a real disconnect between the science of human performance and human potential and the execution. So, I sort of crafted a narrative around being able to understand the science. I did my doctorate in that space. That’s fundamentally how it started. No plan.

And you have a couple of girls; you have a family. Do you apply your high-performance learnings to your kids?

No. Hell no. They wouldn’t listen. They don’t listen. And I think it’s the old adage, “The cobbler’s kids have no shoes.” I try and make sure, maybe use some of the principles I’ve learned over the years, but I can’t get them to eat the right foods. Anything I have to offer is, “Dad’s talking and we’re not paying attention.” That’s probably my greatest performance challenge right now.

“I realized that there was a real disconnect between the science of human performance and human potential and the execution”

I want to talk a little bit about transitions. How do you approach an athlete’s transition from standing on the podium to having to re-enter the mortal world?

You’re not defined by what you do. A lot of our programming and frameworks center around developing you as a human, and the extraordinary area of craft or mastery that you’re involved in will take care of itself. In specifically the transition space, it’s that early recognition of just trying to help develop some set of values or ethos that really define your way of being in the world.

Bluntly having a conversation: no matter how goddamn good you are, you’re going to get beaten at some point at whatever it is you’re trying to do; it doesn’t matter. And even if you do maintain world-class stature, at some point you’re going to be dead. So, it doesn’t really matter. All performances finish, and so what we talk about in particular with those who operate in the highest performing environments that they recognize early, that they have to plan for it. By no means does it work out perfectly, let’s be honest. But it’s at least an early conversation.

Even with all that said and done, it’s still tough. Most of the challenge comes from the idea that when you’re part of a high-performing team, there’s a community of like-minded folk that are around you in that environment. Once you walk out, you’re gone. You literally walk out the door and it’s over. And that’s why I think having a good strategy in place to support that loss is vital, because it is a traumatic loss for most people.

“I want to really spend time working with people I really trust and respect and admire and can learn from, on things that are of meaning and import”

What are you thinking about for your future?

There’s still lots of great stuff to do in my space. I’ve got to a point where I want to really spend time working with people I really trust and respect and admire and I can learn from, on things that are of meaning and import. I think when you’re younger, you can handle working in an environment, to get the experience, that’s not ideal with respect to maybe all the people around you. But now, it’s like I don’t want to waste time working with people who just don’t see how we can help the world. So that narrows the field really quickly.

I think that part of the process, too, is making sure you’re clear on those things that give you energy and support you as much as you’re trying to support others. And in the coaching world, you spend a lot of time in your life helping others. It’s sort of hard to step back and go, “Oh, what do I need right now?”

I find that there’s mental learning and there’s physical learning. How do you work with that?

Letting yourself make a lot of mistakes in the learning process is something more mature people are not good at. And if you try to intellectualize the learning because of your age and your experience, it gets all sideways because the body really likes to learn by doing. And this gets back to this idea of the beginner’s mind; it’s actually great if you can let go of everything and just do without setting expectations. “I want to see this. I want to get there. I’ve taken up ski racing. I want to get down the hill three seconds faster than I did yesterday,” whatever it is. That really confuses the issue. You have to go back to a baby kind of model: “And I just tried to walk. My body just got up and I fell over and my body got up and it fell over again and I fell on my face and I fell on my butt and I fell, and I fell, and I fell.”

Older adults don’t like this. They wonder: “Who’s watching me? Am I a fool?” Whatever. This concern actually convolutes the learning process for a lot of reasons because you’re not focused on the task at hand.

A trick would be, just as you’re skiing down, try and feel what you’re doing. Don’t try and ski. Just try and feel what the legs are feeling. What are the feet feeling? Connect with the body and build that sensing. Allow the body to ask, “Okay, what am I feeling?” And it doesn’t have to be good. It can be: “I missed a gate,” it doesn’t matter. It’s not the feeling about the execution of the task. It’s the actual feeling of what the body’s experiencing as you’re skiing down the mountain. And it’s an interesting perspective to try and get you back to that framework of doing without expectation of outcome.

“Outcomes will get in the way because, in the learning process, the way the brain adapts is independent of the outcome”

This morning I was on a ski simulator over here, which I’ve been on every morning for the last five days. It’s very much that. The consequences are minimal. Like, if you blow it, you just go off the track and you’re in a net, which is a very different level of consequence than if you fall on the hill.

And that might mean, just take it back a notch. Outcomes will get in the way because, in the learning process, the way the brain adapts is independent of the outcome. It adapts to the actual activity and the exercise. So, the movement itself is what you are trying to generate neural networks in the brain for.

Quote of the day: “Outcomes get in the way.”

Exactly. There’s time and place. If you had learned to race as a young kid, you wouldn’t have over-thought it; you would probably have been laughing and having fun. I don’t think it’s that if you learn young, you are better in the long-run. For one: you just learn faster at a young age, and there’s lots of other reasons for that. But two, you have fun with it, you do a lot of it, and you tend to enjoy it. Plus, if you fall on your butt, it doesn’t really matter.

A great lesson from the action-sports world is to celebrate things that are inherently new or have never been done before. Again, taking this into a business setting, innovation is really the only way to push beyond where you’re currently at. If you’re trying to celebrate the outcomes, you end up withdrawing and becoming conservative. If you’re trying to do things that are new, fresh, and exciting, you have to focus on the process a little bit more to allow the outcome to happen because the failure rate will be massive at the beginning — as it should be; failure rate should be extraordinarily high.

I was so crazy fortunate at Red Bull because I was able to sit on other advisory groups and spend days with these action-sports athletes, musicians, artists, dancers and filmmakers all pushing the edge of their creative expression. And then I sat on the board at DARPA for several years, an advisory program and, it was funny: they did the same thing. They have a 90% failure rate there. And with massive strategic outcomes, if you’re going to invent the internet, the pressure is high. The running joke there was: If you don’t invent the internet, you get a B. But they both are so similar when you think about trying to do things that are innovative, never been done before; they’re trying to push the edge of what’s possible. And it’s the same principle. You kind of get caught up and high-five, I got to invent the internet because it doesn’t even exist. I need to invent a communication platform independent of any structures or systems, blah, blah, blah, whatever it is, whatever the brief was, and they sketch it out on a piece of paper. That piece of paper is still on the wall there. It’s ridiculous.

Surfing

Do you surf?

Yeah. Not like I used to. But when I look at my career, I was surfing, like, three times a day and living on the beach, and I did that whole thing. And I would love to get back to that lifestyle some days with no responsibility. But I look at my life and then I spend 10 years with the US Ski & Snowboard team in mountains around the world, learning. And I just look at that; I’ve been so fortunate to deep-dive into things, now I can actually step away.

Literally last week, I went to the World Surf League at the Surf Ranch up here, Kelly’s pool. And it was the same guys and the same old crew that I was saying “good day” to. When I spent time on the tour with the different athletes, I was like, “Wow, I really love that,” and I love the camaraderie, but there’s also a little piece of me was like, “I’m kind of glad I went and tried something else and I didn’t just stay there.”

Andy, what are the three non-negotiables in your life?

I would have to say my family, absolutely. Providing a future for the kids.

Participating in a community of people I trust, like, and admire. That is really moving up on my list of non-negotiables just because what I do must have a purpose to it. For example, we’re looking right now at fine-tuning a high-performance program for young climate leaders and cancer researchers. We want to take what we’ve learned about all these extraordinary performers and point it at people who are solving the world’s biggest problems.

Lastly, health. I don’t want to use the word longevity because I think that’s all confused as shit right now. But I think health and just how I experience the next 20, 30 years of my life is right up there as well now.

Connect with Andy:

Website

LinkedIn

Twitter

Liminal Collective

LEAVE A REPLY

The ideas expressed here are solely the opinions of the author and are not researched or verified by AGEIST LLC, or anyone associated with AGEIST LLC. This material should not be construed as medical advice or recommendation, it is for informational use only. We encourage all readers to discuss with your qualified practitioners the relevance of the application of any of these ideas to your life. The recommendations contained herein are not intended to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease. You should always consult your physician or other qualified health provider before starting any new treatment or stopping any treatment that has been prescribed for you by your physician or other qualified health provider. Please call your doctor or 911 immediately if you think you may have a medical or psychiatric emergency.

Absolutely, terrific article…probably not great English….but smart, helpful, thought provoking, kind and of course, humor….thank you

Andy speaks Australian English

Andy, you encourage people to think. It can’t get better then that

Excellent read. Caused me to consider where I am right now. 63 a new business in a sector I’d have never ever thought I’d be in 5 years ago!

Some good advice in there.