The $5,000 key to a longer life

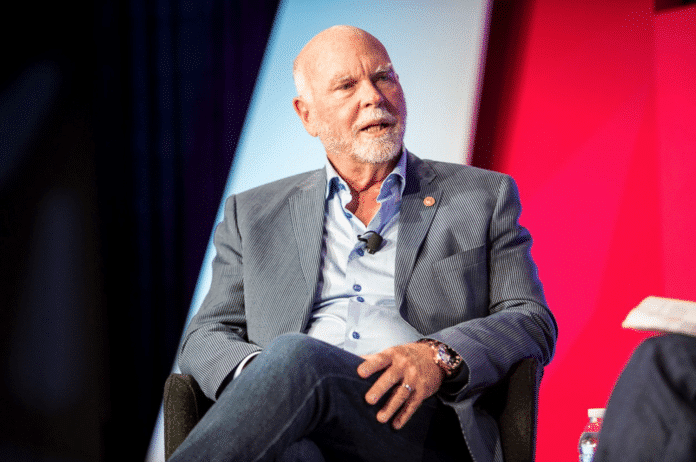

Genetics pioneer Craig Venter says you might not be as healthy as you think. In fact, 30 to 40 percent of the people who come to his company Human Longevity Inc. for a daylong series of scans, tests, and genomic analysis end up finding things they weren’t expecting, including aneurysms and early-stage cancers. But this is good news, Venter says, because it offers an unprecedented opportunity for early intervention that saves lives — the essence of preventative medicine.

Venter has been at the forefront of genetics research for decades. In the late 1990s and early 2000s he essentially eked out a tie with the Human Genome Project in a race to sequence the first human genome, his own. Now Venter is using Human Longevity Inc. to build on genetic knowledge by combining it with ultra-detailed information about phenotypes — the characteristics people display. HLI, based in San Diego, gathers this information by putting customers through a workup called the Health Nucleus, which combines whole genome sequencing with a full-body MRI, metabolic and microbiome analysis, and cognitive testing.

About 2,000 people have gone through at an only-for-early-adopters price of $25,000.

Obsessively detailed screening isn’t widely recommended. Lots of doctors say some of the early cancers HLI finds might never move beyond “stage zero.” But Venter argues that the Health Nucleus will be crucial for increasing longevity, because it finds diseases while they can be treated much more easily. Now HLI is planning to reach many more people by substantially lowering the price. If it’s successful, Venter, 71, might dramatically expand our still-limited knowledge about the genome — just in time, too, since we’re on the verge of editing it. Neo.Life founder Jane Metcalfe sat down with Venter for a chat last week at Startup Health Festival in San Francisco. These highlights of the conversation have been edited for clarity.

Where are we in terms of collecting and parsing the data that will be required to really understand the human genome? Not as far along as most people think. It’s still extremely early. We’re still around 1 percent of the knowledge that will be ultimately obtained. That’s sort of the basis of why we started Human Longevity: we could collect, hopefully, tens of millions of genomes, but in conjunction with having phenotype and clinical records on every person. And we’re using machine learning to make correlations between them. The way genetics has been done for the last century is very slow, tedious, and

I would say at least half if not 80 to 90 percent of the papers published in this field are wrong.

Wow. Our team has found as much of a third of ClinVar, which is the reference that everybody uses for annotating their genomes, is just riddled with false data. If that’s what diagnoses are being made on, that’s why the [genomics] is struggling right now. For people to accept it, you can’t get the same results from two different places. So we hope the next couple years will start to change that, as we get more and more people going through the Health Nucleus.

When you say we understand one percent of the human genome — is that an educated guess, or is that based on something? It’s based on discovering how much we don’t know every day. We’re finding with various genetic disorders, for example with [a type of mutation called] triplet repeats, there were never really broad population [studies] for these. [Researchers] look under the lamp post, so they look at people with that disease. Looking at a much broader population, we’re finding people with numbers of triplet repeats that greatly exceed what would [support] a clinical diagnosis of, for example, Huntington’s disease. But these people clearly do not have Huntington’s disease, they have no family history of it, no symptoms of it. Maybe they’ll get extremely late-onset disease or something.

Then we have another thing with [people carrying a variant known as] APOE e4, which puts them at very high risk for Alzheimer’s. In fact we have one individual, from all the genetic scores you’d be sure this guy would get Alzheimer’s disease. He’s 74 right now and he had almost a perfect brain scan, more like a 40-year-old. So the challenge is the lack of correlation at a 100 percent level between genetics and what we attribute to it. “For some people, it could buy them 90 years, right?” BRCA1 and BRCA2 are another example. It’s actually a 50 percent risk factor for a woman to get breast or ovarian cancer having the well-known changes in those genes, unless there’s family history.

If every woman in your family has breast or ovarian cancer, then, plus those markers, it goes up into the high 90 percent.

So that means there’s other genetic elements that we simply don’t understand yet. And once we do understand them we’ll be able to tell women whether their risk is zero or close to 100 percent. Right now it’s 50/50 because the most important risk factors only come from knowing your family history.

HLI has had about 2,000 subjects who have gotten complete genomic and phenotypic information, with full-body MRIs and cognitive testing. Now you’re rolling out a version that’s $4,950. That’s a big discount from $25,000. At $25,000, I think, to do the Full Monty on yourself as a healthy person was a bit of an indulgence. And it was for the leading edge, people who had lots of money and curiosity. We didn’t know what to charge initially. So the new version is called the HNX. We still have the HNX Platinum that people still ask for, and it’s a full eight-hour one. This takes two and a half hours to go through everything, so it’s a big difference in time and dollar commitment. And you can use health savings plans to pay for this. We’re trying to get enough data where it makes sense for third-party payers to pay for it, but preventative medicine is hard to sell.

But we just did a study on 25 people for a pharma company, sort of average age, and out of 25 people we found one with a very serious cancer that they didn’t know they had. [We also found] a couple with serious heart disease, and a spectrum of other diseases. They would have had to pay for these once they revealed themselves. We’re finding one percent of the population have brain aneurysms. Brain aneurysms: most people know somebody that’s died from one. [With early detection] they can be treated as an outpatient, just threading up a coil to put in them. “It’s like you’re not going to ever change the oil on your car until all the oil drains out and your engine freezes.”

Five percent of people over 50, we’re finding a major tumor that they didn’t know they had.

The good news is we’re finding these at stage zero, stage one, and some at stage two. Thus far they’ve all been successfully treated, all the diagnoses were confirmed by the pathology, so we’re doing really well with diagnosing things in the MRI. And we now have a machine-learning algorithm that’s as good as the best pathologist for scoring a high-grade prostate cancer straight from the MRI. We think in a year we will have the same thing for breast cancer, switching from doing mammography to an MRI for breast cancer, which will be a major shift.

Mammography has a huge false positive and a false negative rate,

so we think getting this data with machine learning is really changing what can happen. Perhaps the most important thing we’re finding is that such a huge percent of the population has greatly elevated organ fat, primarily liver fat. Normal is four percent or less, we’ve had people as high as 38 percent without knowing it. And so we’re trying to estimate how many of those go on for fibrosis and would need liver transplants. We found a correlation between the microbiome and fatty liver, so I think that’s important. It’s a fantastic thing to do on a preventive basis, to find out what may be lurking in your body—a little time bomb or something that you could do something about.

As a consumer, $5,000 is still a fair amount of money. I’m not sure I would come unless there was something wrong with me that I was trying to figure out, in which case I might come to you instead of going to the Mayo Clinic. But that’s the wrong way to think about preventative medicine. It’s like you’re not going to ever change the oil on your car until all the oil drains out and your engine freezes. Because then you know something’s wrong. With these cancers, with the early detection, as I said, we’ve been 100 percent successful thus far in treating them. When you detect cancer from symptoms, the outcome is totally different. You’d be smart to go through [it], because then you become a baseline and then you can detect differences annually in yourself.

I’ll give you an example with myself. I was discovered to have high-grade prostate cancer last December [2016].

And this was after a long period of having elevated PSA [but] having biopsies and being told I didn’t have prostate cancer. Also, one of my blood tests showed that I had extremely low testosterone levels, which is bizarre because nobody’s ever accused me of being low in testosterone. So we’re setting up these new programs as membership programs: once you have some of the tests, you can come back annually, for example, if you have a higher risk for cancer, and just get the whole MRI.

And you’re also increasing your outreach to other organizations to help have this not just be localized in San Diego? Yeah, in fact we’re trying to get several dozen set up in the next year or two around the country. Some are partnerships, some are being done as franchises.

How many genomes would you like to sequence by the end of, let’s say, 2018? Well our goal is as soon as possible to get 10,000 individuals through the Health Nucleus, because that gives us a really good starting data set for the machine learning of comparing all the traits back to the genome.

You wrote an op-ed last month talking about the risks of gene editing, and you’ve been very vociferous about your concern that we are so excited about the potential that we are liable to get ahead of ourselves and start editing the genome prematurely with unintended consequences. Obviously there’s tremendous concern, and that’s actually kind of unusual for you.

I expected you to be out on the fringe of that debate. But how much do we have to understand about the genome before edits that would be passed down in the germline would make sense? If we’re at one percent now, does 50 percent increase your comfort? Does 90 percent increase your comfort? We need tools that are really precise tools. CRISPRs have off-target effects, and usually [researchers] just measure the effect they want to. They don’t re-sequence the whole genome and see what else was changed. I think getting rid of Tay-Sachs disease or Ataxia-telangiectasia in the population wouldn’t be bad ideas …

But can’t we just do that with frozen embryos? Don’t we kind of get around that? Once you start down this road it’s a very slippery slope. In all the polls, most young parents want to change fairly trivial traits in their children, you know, eye color, hair color, types of muscles, versus disease risk. Kay Jamison has written several books about manic-depressive illness and creativity. If we treat manic depression as a disease and we find the genetic links for it, we’ll wipe out all the creativity in the human population by editing that out. So we need to know all the consequences of making changes for future generations.

You’ve signed on as a sponsor for Startup Health’s Longevity Moonshot. And the definition of the Moonshot was, “To increase the average life span by 50 years.” We can prevent a lot of aging through lifestyle choices: tobacco, sugar, alcohol — eliminate the poisons — diet, exercise, sleep, stress. But we have no means of clearing senescent cells or repairing mutated DNA, or what have you. So what do you think are the most promising avenues of research to pursue in the quest for longevity? About 30 percent of people that reach the age of 50 will die before the age of 74 right now. So when you’re talking about increasing a life span, finding a tumor in a 50-year-old that can be completely cured probably changed their life span by 30 or 40 years, if they were going to die from metastatic cancer.

So early detection buys us half of the 50 years that we’re going for? For some people, it could buy them 90 years, right? At the Venter Institute [we had] a 16-year-old girl whose younger brother died at age 12 from a neuroblastoma. On sequencing her genome, she had multiple oncogenes that were mutated, the same as her younger brother, and her parents were sure that she was going to develop cancer. So we set up a program, she’s now 18, a student at UCSD, she comes to HLI every six months for a whole-body MRI with the goal, knowing she’s at risk for cancer, of detecting it at stage zero or stage one.

Last year, NEO.LIFE asked you about your personal longevity strategy. In addition to diet and exercise, sleep and stress reduction, and avoiding toxins as much as possible, you mentioned that you take the diabetes drug metformin, which appears to have longevity benefits in mice. Do you think that’s making a difference, and are there other pharmaceuticals or other ingestibles of some sort? I take statins and they’ve changed my cholesterol levels substantially. With metformin and a combination of diet changes, my A1C [a test of blood sugar] is now at normal levels. So it does have an impact. I do believe in preventative medicine even though I do risky behaviors like drive motorcycles really fast. I now have one of these vests that, if you fly off your motorcycle, inflates instantly so you bounce down the highway instead of … I haven’t tried it yet to see if it works.

You’re in the business of predicting what people’s genomes will say. You probably have the most-studied genome in the world. So how long do you expect to live? It’s interesting because the team is putting a series of algorithms together, and we’re using it to predict the age of your brain. From the rough studies — I’m 71 — they said I have a brain of a 40-year-old. My wife said, “No, he has a brain of a 17-year-old.” But I’ve outlived every male from my father’s side of the family — except my year and a half older brother — by almost a decade now. They all died from heart disease or a combination of heart disease and alcoholism, so I think statins and the preventative measures that I’ve taken have presumably had some effect.

And what would you hope to see? Another 30 years? Another 50 years? The key to longevity is not your [body-mass index], like a lot of people think. It’s your muscle mass. The key is trying to maintain strength. As people get more and more frail, they fall, they break bones, then they get hospitalized, and they sort of start a slippery slope. The data shows that if you can maintain strength and activity — we all have sort of a fixed decline, but it’s a question of “Can we change that slope?” The algorithm for predicting what year you’re going to get Alzheimer’s is really getting pretty accurate. I’m pretty far out on the curve on that, at least 20 or 30 years out, so … if I could still be riding a motorcycle at 120 miles an hour at age 102, I think I’d be happy.

Is that your expectation? I’m going to try.

This interview originally appeared in Neo.Life, our favorite site for smart forward looking life science information. Check them out, get their newsletter, we do.