With the topic of age discrimination in the workplace top of mind, some have assumed that women are impacted more than men. The findings of a recent study may surprise you.

Age discrimination in the office may not affect both genders equally, and in one important respect, older women actually may have an easier time than older men, according to Ashley Martin, an assistant professor of organizational behavior at Stanford Graduate School of Business, who recently published a study about it.

In the study in Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, Martin and colleagues Michael S. North of New York University and Katherine W. Phillips of Columbia University present evidence that older, assertive men face the strongest “agency proscription” — pressure for them not to assert themselves, but to sit back and allow young people to rise. Older women who are similarly assertive, in contrast, tend to be spared such backlash, because their behavior isn’t perceived as threatening.

Intersectional Escape

Martin was intrigued by the possibility that women might slip through the space between biases — a phenomenon called “intersectional escape.” In this middle space, people can sometimes escape traditional biases.

Younger employees may perceive older women as less of a threat to their own careers. They’re also more likely to view older, dominant women as maternal or caring, even if they behave in an assertive way. But these same employees see older men as overly aggressive and hostile to younger workers’ success.

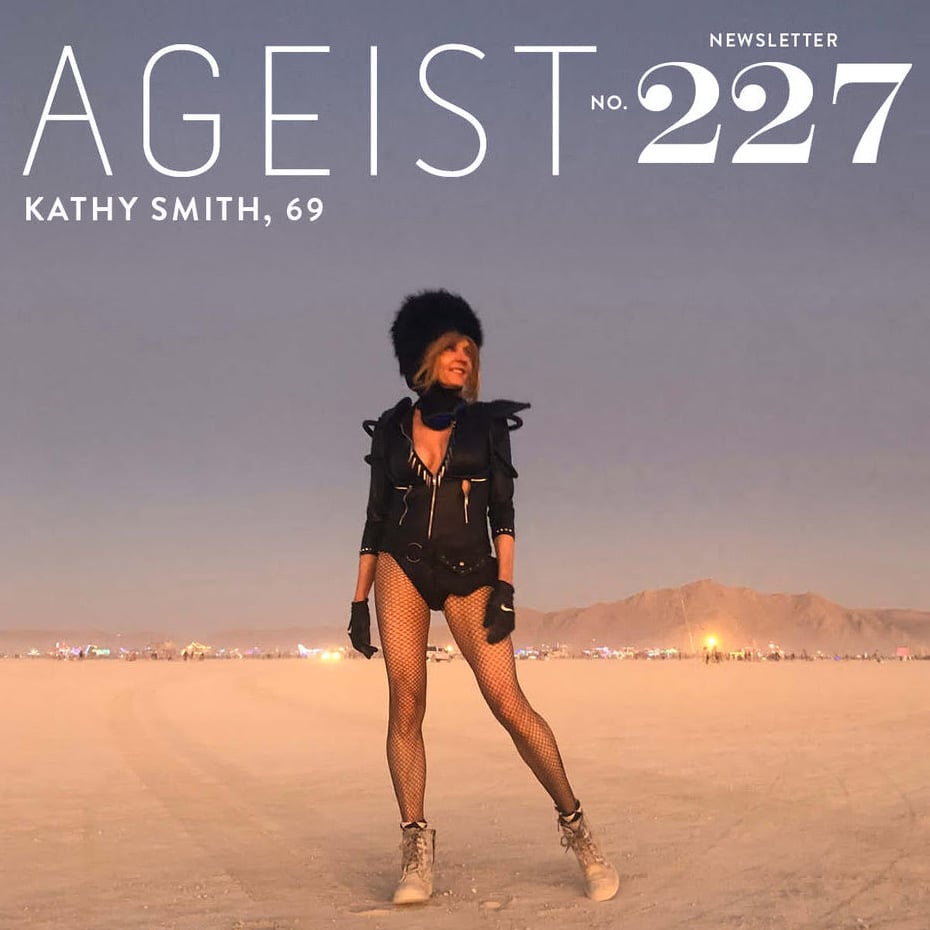

“As a practical matter, we find that with many women, when they hit their mid-50s, it is game-on for them,” says AGEIST founder David Harry Stewart. “This is their time to shine. These are women who are out there in the world, using all the skill sets they have accumulated with running a family while having a career. Suddenly the kids are gone, and they have this tremendous burst of energy to get stuff done.”

Men, says Stewart, have the pressure to achieve at increasingly higher, ultimately unsustainable, levels. “They drop out. They back off. This isn’t necessarily the case wth everyone, and sexism is very much alive, but it is certainly a trend we see with our age group.”

Understanding Gender’s Impact on Ageism

The intersection of age and gender in society was largely uncharted territory, so Martin and her colleagues devised a multi-faceted effort to study the dynamics. In one part of the study, they gathered data on members of Congress and found that women, though underrepresented, tend to take office at older ages than men.

They also surveyed a group of voters after the 2016 presidential election contest between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton and found that the more a voter believed older people should step aside (a form of discrimination), the less likely he or she was to vote for Trump.

The researchers also did a series of experiments, including one in which subjects evaluated resumes of younger and older male and female job candidates, and another in which they were asked to imagine being in a workplace meeting with a 68-year-old male or female coworker, who either dominated the discussion or else let other people take the lead. In the latter, they found that assertive older men received the most negative response, while assertive older women didn’t get that same pushback.

Martin is careful to note that just because older women experience intersectional escape when it comes to ageist behavior, that doesn’t mean that they won’t experience other types of age-related bias.

“Basically, we don’t like older people who are doing young people things,” she says. “If old people come to clubs where young people hang out, they’re like, ‘No, no. I don’t like these old people.’ So there’s an identity bias. There’s also a consumption bias — we don’t want old people using resources, so we don’t think they should get the best seats on the bus or have their own advocacy groups.”

But there’s no indication that those reactions would be any less negative if the older person happens to be female, Martin said.

On the Other Hand

Of course, this is one study. And others have conflicting findings. For example, a 2015 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research — based on what was probably the largest field experiment to date testing the prevalence of age discrimination in hiring —showed that the resumes of older women got far fewer callbacks than those of older men and of younger applicants of either sex.

Study authors David Neumark and Ian Burn of the University of California at Irvine and Patrick Button of Tulane University thought that the way in which hiring discrimination is usually detected — through dummy resumes sent out in response to real job postings — might have been flawed.

So they crafted resumes that more realistically reflected experience that someone older than 45 might have. They then designed fake documents in four job categories, three age brackets and a dozen cities. In all, more than 40,000 resumes went out in response to online job ads — many more than other recent studies on the subject.

Overall, fictional workers aged 49 to 51 got 18 percent fewer callbacks than those aged 29 to 31, and workers aged 64 to 66 got 35 percent fewer callbacks, showing a strong bias against older applicants. But for administrative jobs, using a sample of only female applicants, those aged 49 to 51 got 29 percent fewer callbacks than applicants aged 29 to 31, and workers aged 64 to 66 got 47 percent fewer callbacks. Sales jobs, which had applicants of both genders, also showed a much greater premium on youth for women than for men.

“We find robust evidence of age discrimination in hiring against older women, especially those near retirement age,” according to the study’s authors. “But we find that there is considerably less evidence of age discrimination against men after correcting for the potential biases this study addresses.”

This article is a bunch of misleading garbage. What about middle-aged women vs. middle-aged men competing for entry-level or clerical positions? Men aren’t ‘expected’ to go after such jobs during their middle-age, so many do not. And when they do they never get the job, let alone a call back. However, I [I’m 50] have, out of desperation, applied for such jobs and have NEVER received a call back for any of the positions for which I applied that fit into the above categories. I began reading your article because I anticipated – by its misleading title – that it would actually address the difficulty that middle-aged, under-employed, but over-educated men (like myself) encounter while seeking jobs that pay a ‘living wage.’