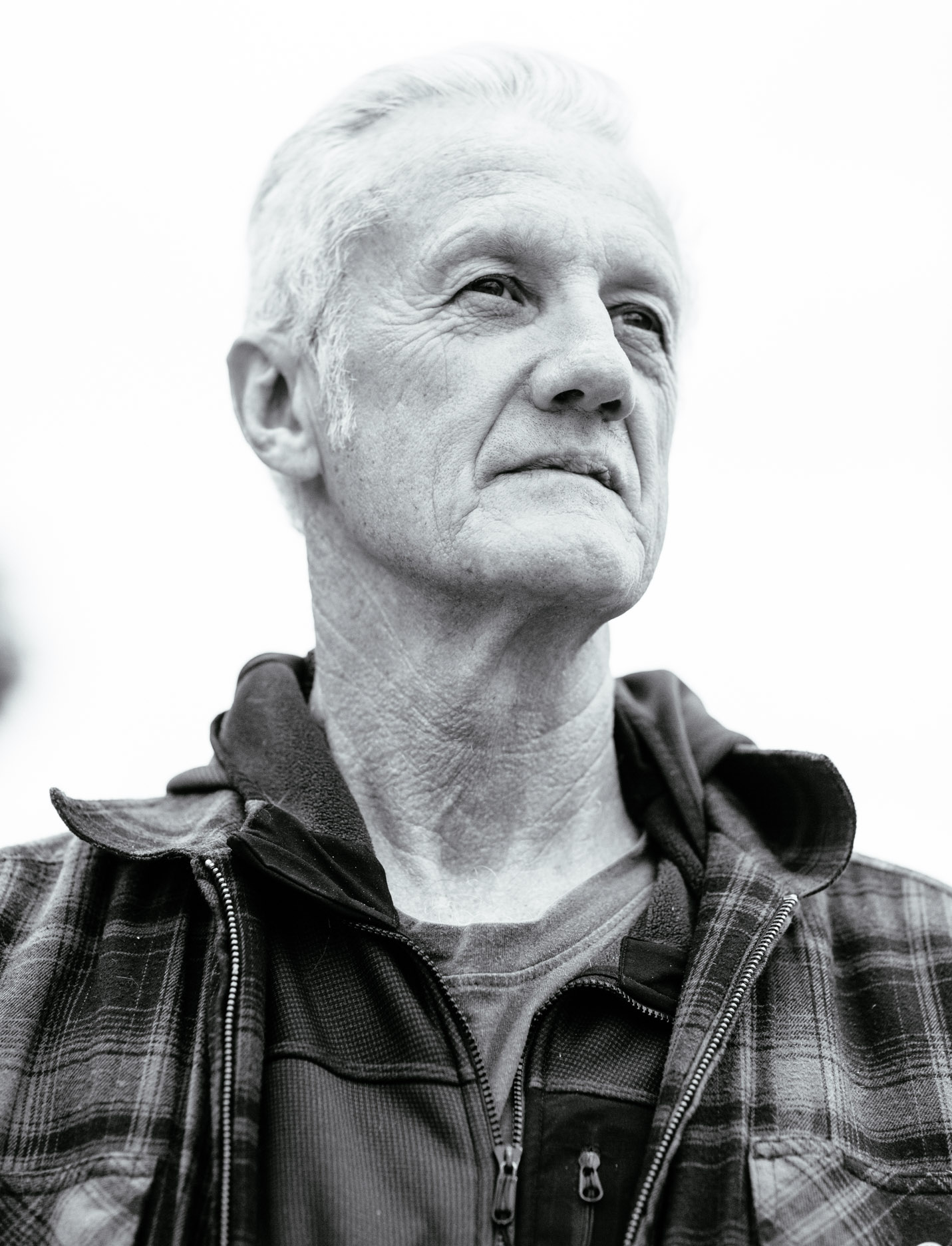

He actually came to Los Angeles to make another movie. But then Gordon Clark, freshly touched down from his native South Africa, met a talkative, warm, young veteran on the street in Santa Monica. Before he knew it, he was traveling across the country to Douglas Brown’s native Louisiana, interviewing those who had served with him during his decade as a sniper in Afghanistan and Iraq.

“It landed in the same way other things land and you go with it. And now I’m reaping the success of it, but it was very difficult at first.”

After being rejected from the Sundance Film Festival, Unknown Distance won the audience award at the Beverly Hills Film Festival this year. But what’s interesting about that above quotation from Gordon is the first part.

Things have been landing for Clark since he first starting sweeping floors, a young man from a broken home, in a Johannesburg hair salon. The journey since has been defined by a willingness to take risks, and yielded enough material to fill several volumes of an autobiography we hope is forthcoming.

It began in Johannesburg in the 1950s, a city ill-suited to a young, curious mind like his. Apartheid’s grip on the country sickened Clark from an early age. When he began documenting its victims with his portrait photography, his hometown became too dangerous for him.

He arrived in America in 1980 with a solid break: The owner of the salon that gave him his first job had gone on to open up franchises in Southern California and wanted Clark and his camera to help with the marketing. He got his green card and soon began focusing on his newfound passion.

“I wanted to be involved in anything that told stories; mostly film,” he told me. “I was very interested in learning about filmmaking. At night, I would go to any seminar, I’d go to anything that could educate me.”

Clark’s obsession would eventually result in a successful career directing commercials, shooting close to 500 in a 14-year period. Then he noticed the market begin to slip. Brands weren’t buying up chunks of TV time anymore and spending lavishly on cutting edge advertising. Those who had managed a successful transition into film — Spike Jonze, Michael Bay — were few and far between. And Clark felt he had so much more to say.

So he took the money he didn’t spend and built a house for himself in Cape Town for a fraction of what it would’ve cost in LA and moved his mother onto the property as well. He was 51. And he finally felt free.

“I started really making images, movies and documentaries,” he says. “That was the liberating part, because then you really start finding yourself in the middle of everything. You find out who you are. And you start contradicting yourself.”

And that’s ultimately the space in which Clark likes to live. After the gloss of the commercial world, he wanted to feel his “moral fiber” challenged. He followed around a street kid from the hard-bitten Cape Flats ghetto, and turned his story into a short film. Again, on the street, he met Leon Botha, an artist suffering from the rapid-aging syndrome progeria.

“A lot of it I learned from Leon, watching him die. Because nothing is ever the same, everything does evolve,” he says. “And I think that’s what drove me to keep going. And now I’m even more driven to keep going.”

There isn’t a massive market for documentaries about soldiers suffering from the moral trauma of war. Clark knew all that before he began following Douglas Brown around, but it still didn’t deter him. When the money eventually ran dry, he dipped into his savings to finish the rest of it.

“The guys were getting impatient and I couldn’t keep them hanging on,” he says. “The suicide rates are like 23 [veterans] a day. More soldiers returning from Iraq and Afghanistan have committed suicide than have died in those two wars together. So that’s what got me. I thought … I couldn’t let him down.”

Childless, Clark says the 32-year-old ex-Marine sniper is “my child now — managing him is like having a pet cobra that’s running loose in your living room all day long.” And you can feel the emotional connection he makes with every one of his subjects, be it a Cape Townian street kid or a physically tortured artist. They benefit from his images and art, yes, but he does as well — it’s what keeps him fueled.

“You just have to know there’s going to be ups and downs, and you’re going to deal with both and it’s okay. It’s like me saying to you: ‘You’re going to jump in the water and you’re not going to get wet.’ Not: ‘You have to take that on, and when you take that on, then that courage will drive you. There are times you’ll feel down. You just have to fight through it.’ There’s a South African saying, vasbyt — bite hard. Because when you get to the other side of it, that’s when you create wealth within yourself. Because you’re understanding the human dynamics of being on this planet. And that’s very important.”

The ideas expressed here are solely the opinions of the author and are not researched or verified by AGEIST LLC, or anyone associated with AGEIST LLC. This material should not be construed as medical advice or recommendation, it is for informational use only. We encourage all readers to discuss with your qualified practitioners the relevance of the application of any of these ideas to your life. The recommendations contained herein are not intended to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease. You should always consult your physician or other qualified health provider before starting any new treatment or stopping any treatment that has been prescribed for you by your physician or other qualified health provider. Please call your doctor or 911 immediately if you think you may have a medical or psychiatric emergency.