Stocking Up

The world today is filled with risks everywhere we look. This has given younger people some pause when thinking about investing. We, however, have been through a lot, and seem to have a better view of the long game. For us, the very nature of what it means to be our age has changed, so it also makes sense that our investing strategies are changing.

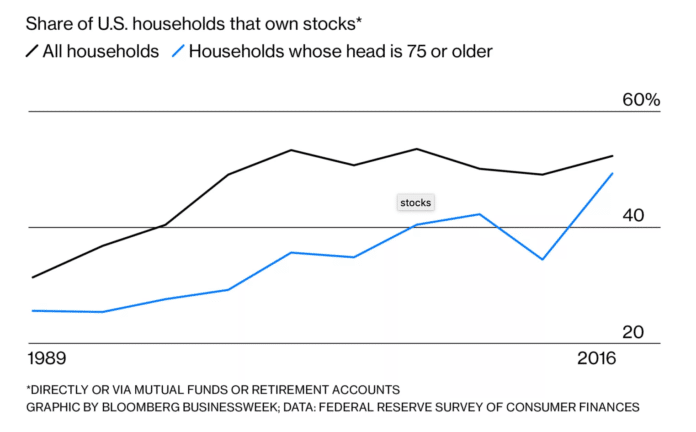

Though US stocks have tripled in value in the last few years, many haven’t been able to take advantage, as they opted out (and stayed out) during the brutal crash a decade ago. There is one, curious, exception though: households headed by those 75 and older, according to the Federal Reserve (and coming to AGEIST via Bloomberg Businessweek). Almost 49 percent of them own stocks. The reasons why vary — many depend on those investments for income and emergency expenses — but what’s clear is this: the idea that we’ll all retire comfortably on a pension has vanished. Those in the 75-bracket (and even earlier, 58 percent of those between 55 and 64 own stock) have experience in both bull and bear markets as well as an ability to build up a nest egg. This has made them more risk-friendly than most (pity the young families still saddled by student debt, or workers who haven’t seen wage increases in years).

“Another reason 75 and older might be investing in stocks is that they see their friends and colleagues still quite active; nothing like their parents at age 75 plus,” our financial guru Scott Brewster of Brewster Financial Planning told us when we asked him to weigh in. “They are now seeing that they might still have decades of active living yet and want the potential for better returns to support a higher quality of life.”

So what advice would he give those active in the market? Or those looking to get in? “A person with a good tolerance for risk, and has other income covering their cash flow needs such as rental income, pension, and social security, might be able to have a higher allocation to stocks than typical for a 75-year-old. On the other hand, anyone who dreads risk, and needs every penny of their investments, probably should have a much lower allocation to stocks. Only in rare instances would I say no allocation to stocks.”

We’re not one to proselytize one form of long-term investment over another (hell, we’re still kicking ourselves for not buying in SoHo in the 1980s), but we love the idea of wealth of experience leading to clever, risk-friendly behavior in this current climate.